For its sixth consecutive annual conference, the International Summit on the Teaching Profession will convene in Berlin on March 3-4. It should be a sparkling triumph for the German hosts. Just a little over a quarter century since re-unification, Germany is now the most admired country in the world. (1) When it comes to environmental sustainability, economic prowess, and hospitality to refugees, Germany far outranks most nations. (2) Germany has not aimed to “Race to the Top,” but instead has used strategies without a trace of nationalism. (3) To top it off, just-released surveys show that Germans are happy, non-materialistic, and find meaning and fulfillment in their work. (4)

Seventy years ago Germany stood in ashes at the end of the Second World War. My grandfather, also named Dennis Shirley, fought in 10 campaigns against the Germans. But it’s not my grandfather’s Germany any longer. A peaceful, democratic, and increasingly multicultural society provides ideas for others on how to ascend the peaks of educational change that stand before us.

When results were first posted from the Program of International Student Assessment (PISA) of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) 15 years ago, Germany was below average in the three areas of mathematics, reading, and science. Since then Germany is one of the few nations that has shown steady and continuous improvements. It has done this while incorporating 5 new states from relatively impoverished East Germany and transforming itself into a cosmopolitan hub in which one of out of every seven people was born outside of Germany.

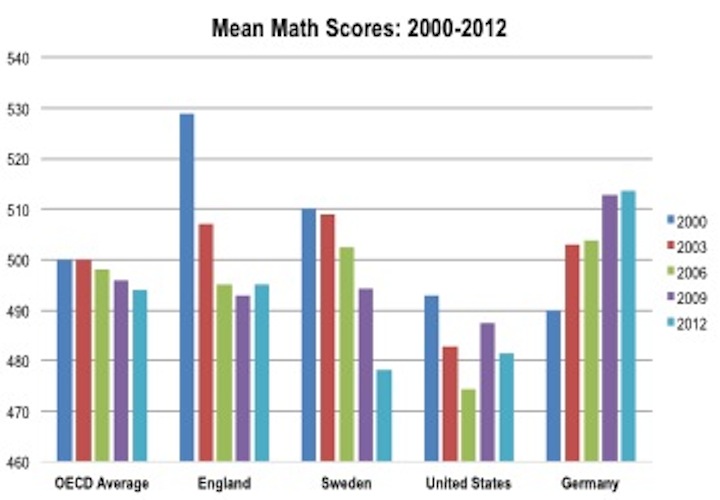

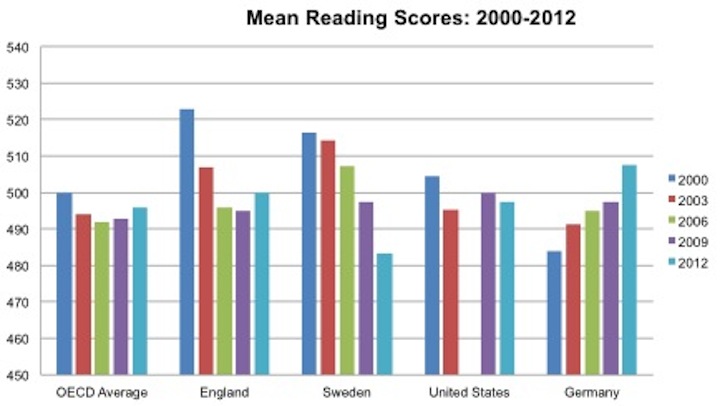

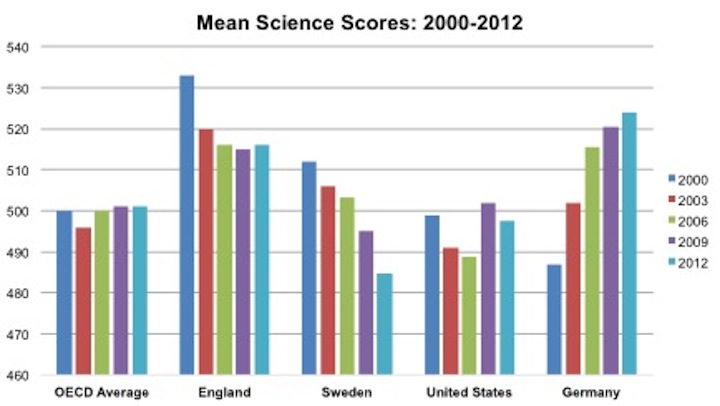

Along with Finland, Canada, and Singapore, Germany provides a counter-narrative to the Global Education Reform Movement or GERM. (5) As described by Pasi Sahlberg, the GERM has emphasized markets, accountability, testing, and privatization in educational change. (6) The leading nations of the GERM have been England, Sweden, and the US. How do their results compare to Germany’s PISA scores? The tables below provide a summary of the evidence. (7)

Figure 1. PISA Math Scores for the OECD, England, Sweden, the US and Germany 2000-2012

Figure 2. PISA Reading Scores for the OECD, England, Sweden, the US and Germany 2000-2012. PISA 2006 results for the US are not available due to sampling errors.

Figure 3. PISA Science Scores for England, Sweden, the US and Germany 2000-2012

In the 3 areas of mathematics, reading, and science the results for England, Sweden, and the US have either declined, in some cases dramatically, or failed to improve. In these nations the public school system has been or is being dismantled. Policies drawn from neoclassical economists have promoted different kinds of semi-privatized systems competing with one another. Academies (in England), free schools (Sweden), and charter schools (the US) now are favored recipients of government largesse and private donations. Teacher education and schools in general are becoming more disconnected from universities, so that the linkage between research and practice is weakened. Government “devolves.” Its role becomes more about doling out taxpayers’ money to service providers, some of whom are for-profit businesses, and then testing students for purposes of accountability. Ultimately, the ability of governments to directly improve schooling is limited. In such contexts of pervasive rivalry it is impossible to have an education system with mutually supportive components.

In terms of political clout, the biggest losers from these policies in England, Sweden, and the US have been democratically elected public authorities, teacher unions, and universities. In terms of learning, it’s the students who have suffered most. This is not always evident to the public because in some cases academies, free schools, or charters, have garnered impressive results in England, Sweden, and the US respectively. But these have been pockets of excellence. You can’t create an education sector where the whole is better than the sum of its parts, because the GERM ensemble of change policies makes it so difficult for the parts to help one another to get better.

What has Germany done to improve its results by comparison?

Mindful of the twin catastrophes of Nazism and communism in the twentieth century, Germans have chosen not to compromise democratic governance of their public schools and their authorities. There has been no frontal assault on public education the way that there has been in England, Sweden, and the US. Nor have Germans severed the ties between universities and schools. German teacher education programs universally require a full two years of teaching internship, longer than anywhere else in the world. German educators are highly educated civil servants, famous for incorruptibility. When Germans have tinkered with alternative routes into teaching, such as their analogue to “Teach for America” entitled “Teach First Germany,” graduates are only placed in classrooms as teachers’ aides, not as teachers of record.

In the wake of the first poor PISA showing, the German government responded by plowing millions of new euros into teachers’ professional development. Before the Common Core in the US, Germany’s “Cultural Ministers’ Council” established standards that cut across all 16 of the German states. It did not, however, build up a massive testing regime that would cut out creativity, physical education, and the arts in the name of accountability. The profession maintained control of the curriculum. As a result, students are only tested on national examinations at grades 3 and 8, and only in German, mathematics, or both. Schools’ testing results are not posted prominently in the local newspapers. A mantra of “transparency” is not used as a rationale to humiliate teachers with low results who work in the most challenging schools.

Civil society organizations have played positive roles in picking up the tempo of school improvement in Germany. The German School Academy sponsors annual competitions among schools on indicators related to diversity, student leadership, and cooperative skills that go far beyond test score results. (8) The “One Square Kilometer of Education” initiative, which started in Berlin and has spanned out across the country, has similar principles to the Harlem Children’s Zone in the US, but works only with traditional public schools, since there is no German equivalent to charters. (9)

Germans will assure you that their system is far from perfect. In an anachronistic retention of nineteenth century traditions, students are tracked at a very young age. The classical Gymanasia that prepares students for university recently cut back their offerings by 1 year to bring them into alignment with international norms of 12 years of schooling, but they did so without reducing the curriculum. This has created enormous stressors for students and teachers alike. Most seriously, German schools are struggling to welcome over 198,000 refugee children of school age who arrived in 2015. No one is quite sure of what the future holds. This is a country, on a continent, in the midst of change.

All of this dynamism will make for a Summit in Berlin with enormous stakes for the future. Education International, representing 32.5 million educators from around the world, has worked with German hosts to sponsor visits to schools with large numbers of refugee children on the day before the Summit. (10) I will take part in these visits. If you would like to follow my reflections, I will be sending out twitter messages throughout the Summit.

The Summit was born of the idea that governments and professional associations need to learn from one another across nations to get better. The inspiration for the Summit was exactly right. It is incumbent upon all educators now, wherever we find ourselves, to break down the cultural barriers that separate us. We should be especially curious to learn from those nations, like Germany, who have put in place policies that have led to steady progress over time. For beyond PISA lie still other, far mightier Summits of human rights, dignity, and inclusion for all that are the real peaks of educational change.

Endnotes:

- A survey by the BBC in 2013 indicated Germany was the most popular country in the world: http://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-22624104. A 2014 survey by the Danish firm Anholt-Gfk found Germany was the world’s favorite country: http://www.usnews.com/news/best-countries/articles/2016-01-20/germany-is-seen-as-the-no-1-country-in-the-world. A 2016 US News & World Report survey gave Germany the number 1 ranking: http://www.usnews.com/news/best-countries/articles/2016-01-20/germany-is-seen-as-the-no-1-country-in-the-world.

- Ecowatch lists Germany as number 5 on environmental sustainability: http://ecowatch.com/2014/10/21/top-greenest-countries-in-world/. Germany has the largest economy in Europe and the world’s fourth largest economy: https://www.tatsachen-ueber-deutschland.de/en/categories/business-innovation. In 2014 Germany became home to one of every five asylum seekers in the world: http://www.fpri.org/articles/2015/05/germany-21st-century-part-iii-who-german.

- Germans learned to distrust nationalism after the Second World War, except for what Jürgen Habermas calls a “constitutional patriotism” of shared moral responsibility. On patriotism in Germany, see http://www.dw.com/en/opinion-no-future-for-nationalism/a-17755767.

- The Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin and the social research group infas interviews with over 3000 Germans revealing these trends. See www.zeit.de/das-vermaechntis. This was the cover story in the 18 February 2016 issue of Die Zeit.

- On Finland, Canada, and Singapore, see Hargreaves, A., and Shirley, D. (2012) The Global Fourth Way: The Quest for Educational Excellence (Thousand Oakes, CA: Corwin).

- Sahlberg, P. (2016) Finnish Lessons 2.0 (New York: Teachers College Press).

- 2000 data for the OCED average, Sweden, the US, and Germany are taken from the National Center for Education Statistics, Highlights From the 2000 Program for International Student Assessment of the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) National Center for Education Statistics Office of Educational Research and Improvement, NCES 2002–116. (Washington, DC: US Department of Education) 4, 9.2000 data for England are taken from Gill, B., Dunn, M. & Goddard, E., Student Achievement in England: Results in Reading, Mathematical and Scientific Literacy among 15 year olds from OECD PISA 2000 Study. (London: Social Survey Division of the Office for National Statistics), 28, 43, 53. 2003 data for the OECD average, Sweden, the US, and Germany are taken from OECD, Learning for Tomorrow’s World—First Results from PISA 2003 (Paris: OECD, 2004), 45, 273, 281, 294. English data was not included in Learning for Tomorrow’s World because the OECD determined that the United Kingdom did not meet its technical standards for PISA 2003. Researchers at the Southampton Statistical Sciences Research Institute have advanced a persuasive argument that the English data are trustworthy, and those numbers are reported here. See Micklewright, J. & Schnepf, S.V., Response Bias in England in PISA 2000 and 2003. (London: Department for Education and Skills, 2003), 56, 59. 2006 data for the OECD average, Sweden, the US, and Germany are taken from OECD, Science Competencies for Tomorrow’s World Executive Summary (Paris: OECD), pp. 22, 47, 48, 53. English data are taken from Bradshaw, J., Sturman, L., Vappula, H., Ager, R., & Wheater, R., Achievement of 15-Year-Olds in England: PISA 2006 National Report (London: Department for Children, Schools, and Families), 19, 28, 33. The US did not meeting OECD technical requirements for reading in 2006. 2009 data for the OECD average, Sweden, the US, and Germany are taken from OECD, PISA 2009 Results: Executive Summary (Paris: OECD), p. 8. English data are taken from Bradshaw, J., Ager, R., Burge, B., & Wheater, R., PISA 2009: Achievement of 15-year-olds in England (London: National Foundation for Educational Research), 26, 29, 32. 2012 data for the OECD average, Sweden, the US, and Germany are taken from OECD, PISA 2012 Results in Focus: What 15-year-olds Know and What They Can do with What They Know (Paris: France), 5. English results are taken from OECD, Country Notes, Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) Results from PISA 2012: United Kingdom (Paris: France), 2-3.

- On the German School Academy, go to: http://www.bosch-stiftung.de/content/language2/html/the-german-school-academy.asp.

- On the One Square Kilometer of Education, go to: http://www.ein-quadratkilometer-bildung.org/stiftung/english/.

- For more information on Education International, go to: www.ei-ie.org.

The ideas contained in this blog will be explored more fully in my forthcoming book entitled The New Imperatives of Educational Change: Achievement with Integrity (New York: Routledge, 2016). If you would like an email notifying you when this book is available, please sign up on my website at www.dennisshirley.com.

: